Film screening shows horrors of Sierra Leone civil war and raises questions about culpability

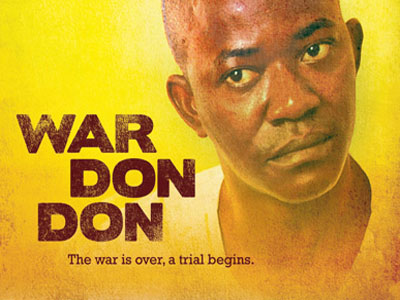

The poster for the film “War Don Don,” which tells the story of Issa Sesay and the Sierra Leone civil war. It was screened at Iona on March 8.

March 29, 2011

How much blame can be placed on one person for the crimes of many others?

This is the central question of “War Don Don,” a powerful documentary that follows the trial and prosecution of Issa Sesay, a commander of the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) in Sierra Leone during its time of brutal civil war.

The film, which was screened at Iona on March 8, discusses Sesay’s and the RUF’s involvement in horrific atrocities against their own Sierra Leoneans, such as rape, mutilation, and kidnapping children.

“War Don Don” begins by showing the Sierra Leonean Special Court finding Sesay guilty of a variety of crimes and human rights violations. The film then backtracks from there to do an in-depth analysis of the RUF, the civil war, the court system that was established in Sierra Leone, Sesay and the charges filed against him.

The RUF was a rebel army whose supposed goal was to fight against corruption in the Sierra Leone government. People originally embraced the RUF because of horrible living conditions and a lack of basic rights. If this was ever truly their goal, something went wrong along the way, as they began to turn on their own people, who they were supposedly protecting and defending.

Women were raped, people were amputated and mutilated, and children were kidnapped and forced to become child soldiers. One witness in the trial even recounted how RUF soldiers brought her to a pile of dead bodies and forced her to laugh at them.

Sesay was second in command of the RUF, and was accused of being the senior commander in charge of child soldiers and the rape of women.

Throughout the film, footage is shown of Sesay’s trial. He never appears nervous or remorseful; he even seemed to display an attitude of nonchalance or smugness. “I looked into his eyes at the opening statements and saw no soul,” Chief Prosecutor David Crane said. In the beginning of the film, it seems that Sesay will be the clear-cut villain, and that the whole trial and court system is cut and dry. However, as the film goes, serious questions are raised about the legitimacy and fairness of Sesay’s trial.

One issue that was discussed is the witness’ testimonies. In many cases, the only way to get enough evidence and testimony against some criminals was to use their comrades and colleagues. These people would not willingly implicate their fellow soldiers with no possible reward, so it is implied that some war criminals would testify against others in exchange for money, protection and/or amnesty. Crane even admitted that the witnesses are not good people but that choices needed to be made in order to prosecute some of the criminals.

Crane is also criticized for specifically targeting Sesay. Crane and the court “chose people who bore the greatest responsibility first, then found evidence later,” Lead Defense Attorney Wayne Jordash said.

The film also implies that there is much fault on the side of the Sierra Leone government. RUF spokesperson Eldred Collins stated in the film that the RUF does not kill Sierra Leoneans and that this claim is propaganda from the government. The government also imprisoned and held suspected war criminals for years before they were allowed to meet with lawyers.

This is one of the main reasons that a special court was set up by the United Nations. Because of the severity of the civil war and a lack of funds, the court could not be run only by Sierra Leoneans. The Court began because of a request from the president of Sierra Leone through the UN.

In the end, after five years on trial, Sesay is found guilty of 16 of the 18 charges against him. The prosecution requests 60 years, while the defense says he is being demonized and requests 10 to 15 years. Each separate count gets Sesay at least 30 years, but they are allowed to be served concurrently, so he gets 52 years, which was the longest out of any RUF officer. His sentence was upheld on appeal, but Sesay insists that if he was charged truly as an individual and not a scapegoat for the entire RUF, he would have only been convicted of a child soldiers charge.

Though it seems obvious at first that Sesay is at fault and deserves the maximum prison sentence, the film really makes you question the fairness and legitimacy of the trial and the entire court process.

A continuation of this event was held later on the night of March 8, as Iona was visited by Special Court Prosecutor Christopher Santora. Santora discussed the events of the film and also shed some light on what was not included in the film. For instance, the film did not tackle the issue of the diamond trade, which is a huge, complex factor of the Sierra Leone civil war.

Santora discussed a variety of topics related to the film and beyond, mainly taking questions from guests rather than lecturing. But one of his main points early on was that the international justice field is still new. While international courts are expensive, Santora said that they had a good track record and that conflicts remained unsolved without international courts.

Santora is currently a prosecutor in the case against Liberian president Charles Taylor. Santora discussed Taylor’s involvement and influence in the Sierra Leone civil war because Liberia and Sierra are intricately connected.

Santora answered many questions from students and teachers, ranging in topic from child soldiers, how witnesses were chosen, how the relationship between different West African nations works, and how his experiences in Sierra Leone affected him personally.